Scientists owe it to the general public to convey their results accurately and honestly.

Over the last week, I — along with most of my astronomer and planetary scientist colleagues — received emails, texts, and phone calls from family, friends, and the media. Everyone was asking the same question: "Did we really find evidence of life on a planet outside of our own solar system?" This outpouring of communication was prompted by a recent article published by The New York Times entitled "Astronomers Detect a Possible Signature of Life on a Distant Planet."

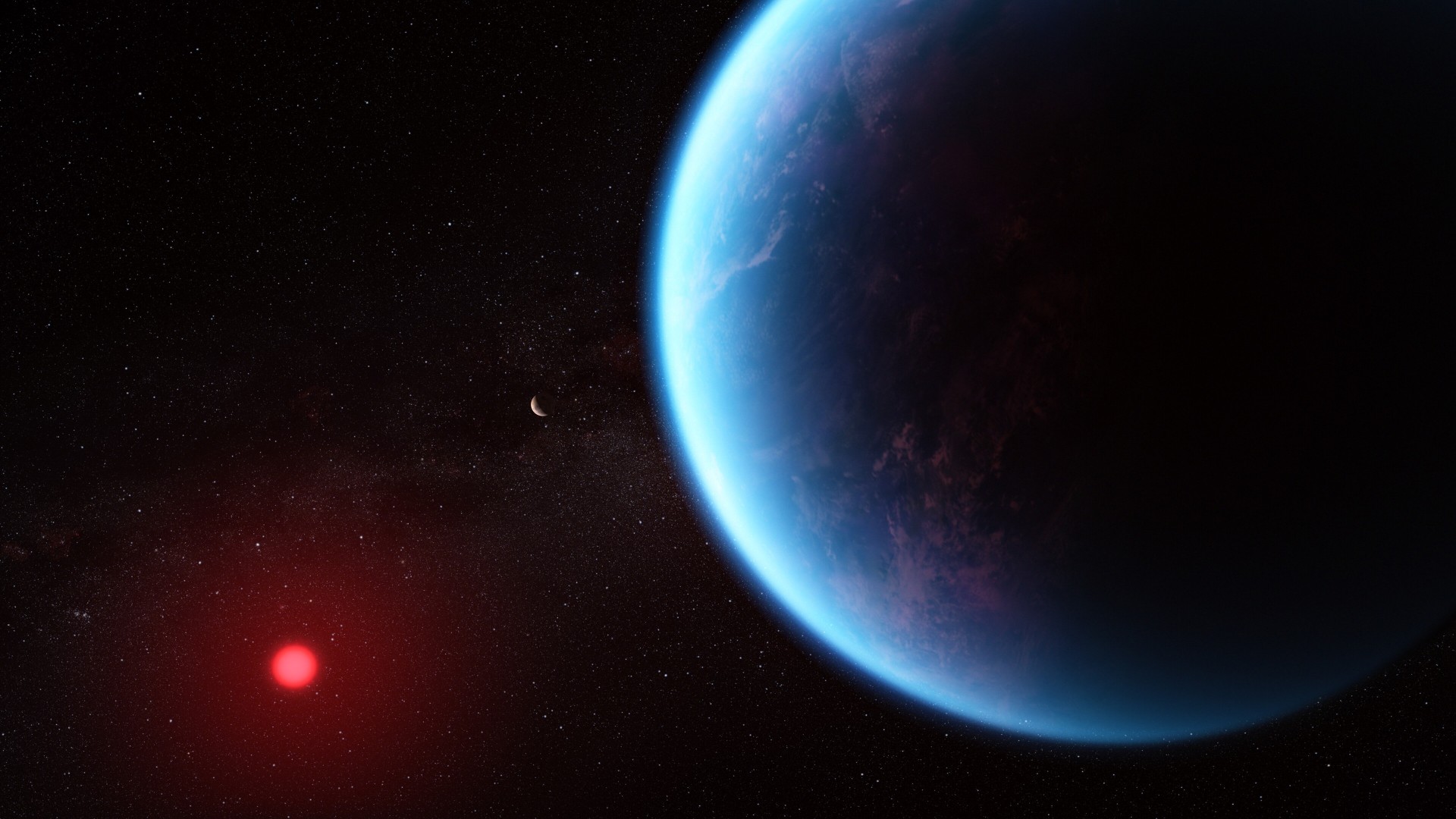

The Astrophysical Journal Letters recently published an article entitled "New Constraints on DMS and DMDS in the Atmosphere of K2-18 b from JWST MIRI." The peer-reviewed article reported a detection — albeit at low statistical significance — of the presence of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and/or dimethyl disulfide (DMDS). DMS and DMDS can be produced both by living organisms (such as phytoplankton) or from run-of-the-mill chemical reactions that are not associated with life at all. However, the authors issued a press release only focused on aliens.

If this news article was a wildfire spreading out of control, then every astronomer was a firefighter, desperately trying to minimize the damage spurred by the press release accompanying the paper. Why? Because the news article was exaggerated.

This tale is not new to astronomers. In fact, it has played out over and over again: fossilized microbes were found on Mars (nope), an interstellar interloper was an alien spaceship (nope), and bacterial life exists in the clouds of Venus (to be tested), to name a few of our own wolves.

As a collective, we can't resist anthropomorphizing the natural world. Many cultures thought there was a man in the moon, until we learned that his face was a series of craters. In 1976, the Viking 1 orbiter took a photo of a face on Mars, which turned out to be an optical illusion of shadows on a hill. These claims highlight the delicate balance between philosophy and science. In philosophy, we can conceptually explore our existence and place in the universe. In science, we need hard evidence.

Since its foundation, NASA has been a constant source of support for the development and the launch of observatories designed to figure out if we are alone in the universe. We want to understand if terrestrial planets orbiting other distant stars could harbor life. In December 2021, NASA launched the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is dedicating hundreds of hours to observing these planets to determine whether or not they have atmospheres.

We want to understand if Jupiter's moon Europa has a liquid ocean with more water than all of Earth's oceans combined hidden below its icy surface. In October 2024, NASA launched Europa Clipper, which will determine the thickness of this outer icy layer and characterize the Galilean moon's overall geology.

We want to understand if Saturn's moon Titan has the proper composition to support prebiotic chemistry. In April 2024, NASA approved the Dragonfly mission, a car-sized nuclear-powered drone, to fly over and land on Titan with an estimated 2028 launch. Dragonfly will measure the composition of Titan up close and search for chemical signatures that could indicate the presence of life.

All of these great observatories will help us to understand fundamental truths about celestial bodies. But if we want to answer one of humanity's oldest questions — are we alone? — then we have to be able to communicate our results. Our ability to trust real scientific discoveries is crumbling under the weight of those who want to be "the first," undermining the efforts of thousands of scientists and engineers pursuing truths with due diligence and following the rules of the scientific method we learned in elementary school. When people believe that we have found life on other planets when we have not, we've lost more than public trust — we've lost our own direction.

Flying to Europa or Titan, and looking at the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, are no longer the subject of fantastical science fiction stories. These aren't dreams. This is all of our present-day reality, and even some of our day jobs. When we sit at our desks and analyze data from these observatories, we are inching toward the answer we want so badly. But over-sensationalizing at best — and even outright lying at worst — about the results of these observatories erodes public trust and ultimately harms the very institutions working in the pursuit of scientific discovery.

This comes at a critical time, when the White House has proposed to slash NASA's science budget by nearly 50% and the National Science Foundation's (NSF) budget by up to 50%. Cutting these programs isn't just shortsighted — it's self-destructive. NASA and NSF fund science across all disciplines. Both agencies have long led and participated in global efforts to pursue scientific breakthroughs, like JWST.

Related: The search for alien life

With these proposed budget cuts, we risk losing the scientists and engineers whose research is the foundation for future mission development.

We risk losing the ability to support and train the next generation of scientists.

We risk missing the very voices that could guide us through our most profound discoveries.

We risk losing touch with our fundamental nature to ask and answer questions about our place in the universe.

The search for life beyond Earth has been an ongoing endeavor since the first philosopher questioned if we are alone in the universe. It relies on our ability to connect astronomy, biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, and even philosophy, which initially paved the way for scientific thinking. From all of these angles, we will continue to pursue an answer to this age-old question.

Yet, in our endeavor, we must remember that our mission is greater than the research of the individual. We must not stoop to using over-sensationalized results to support our own personal agendas. And, we must not forget our collective direction: the pursuit of truths and our responsibility to share these truths — and only these truths — with humanity.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments