A new gas giant world discovered by citizen scientists using data from NASA's exoplanet-hunting spacecraft TESS is cool, literally and figuratively.

The extrasolar planet, or "exoplanet," designated TOI-4465 b is located around 400 light-years from Earth. It has a mass of around six times that of Jupiter, and it's around 1.25 times as wide as the solar system's largest planet. What is really exciting about TOI-4465 b, however, is the fact that it circles its star at a distance of around 0.4 times the distance between Earth and the sun in a flattened or "elliptical" orbit. One year for this planet takes around 102 Earth days to complete. Its distance from its star gives it an estimated temperature of between 200 and 400 degrees Fahrenheit (93 to 204 degrees Celsius).

This makes TOI-4465 b a rare case of a giant planet that is large, massive, dense, and relatively cool, existing in an underexplored region around its star in terms of what we know about planet size and mass.

Planets like TOI-4465 b are cool prospects for exoplanet scientists to study because they bridge the gap between "hot Jupiters," scorching planets that orbit so close to their stars that their years last a matter of hours, and frigid ice giant worlds like the solar system's own Neptune and Uranus.

Unfortunately, we don't know of many such worlds because they are difficult to detect.

"This discovery is important because long-period exoplanets, defined as having orbital periods longer than 100 days, are difficult to detect and confirm due to limited observational opportunities and resources," team leader and University of Mexico researcher Zahra Essack said in a statement. "As a result, they are underrepresented in our current catalog of exoplanets.

"Studying these long-period planets gives us insights into how planetary systems form and evolve under more moderate conditions.”

The rarity of such exoplanets makes TOI-4465 b a prime target for future investigation with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). But just how did the JWST's sibling, NASA spacecraft, TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), detect such an elusive planet to begin with?

Don't cross TESS. Astronomers will hunt you down

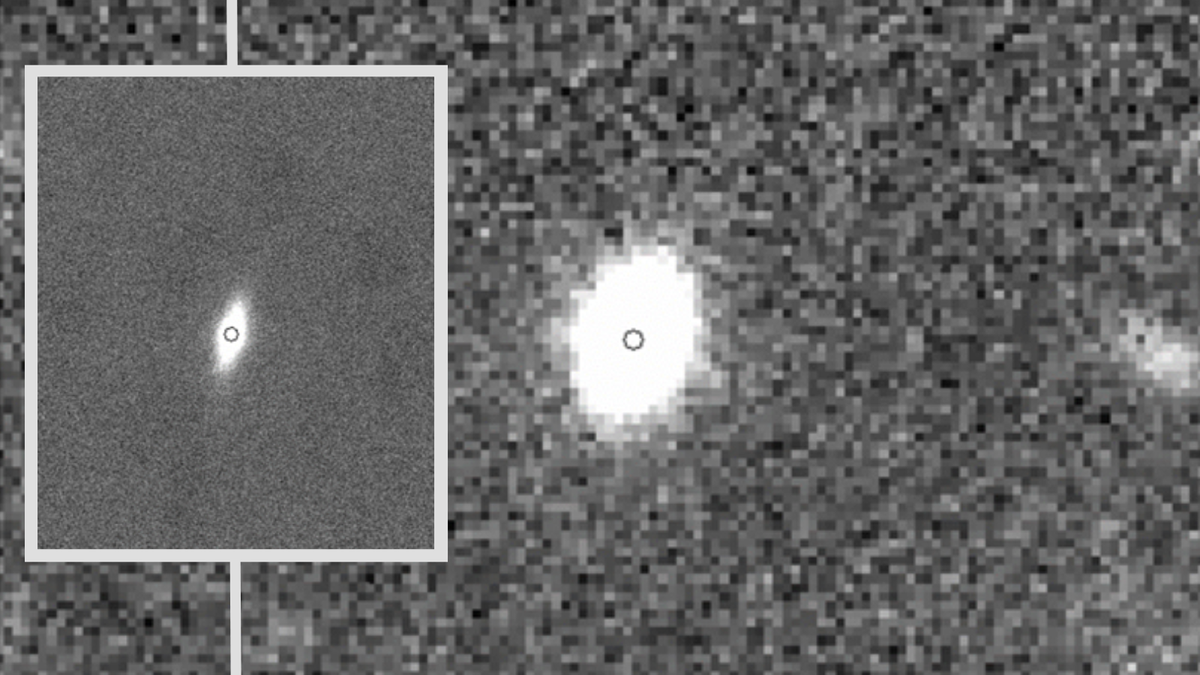

TESS detects planets when they "transit" the face of their parent star, meaning they cross between their star and Earth. This causes a tiny dip in the light received from that star.

TOI-4465 b was spotted by TESS during a single fleeting transit event. That meant, in order to confirm this planet, the team needed to observe at least one more transit event. Something easier said than done due to some frustrating complications.

"The observational windows are extremely limited," Essack explained. "Each transit lasts about 12 hours, but it is incredibly rare to get 12 full hours of dark, clear skies in one location. The difficulty of observing the transit is compounded by weather, telescope availability, and the need for continuous coverage.”

To combat these issues, the team turned to the Unistellar Citizen Science Network, calling upon 24 of its citizen scientists across 10 countries. These amateur astronomers used their personal telescopes to observe TOI-4465 b's host star.

Combining this data with observations from several professional observatories resulted in the discovery of that elusive second transit, thus confirming TOI-4465 b.

"The discovery and confirmation of TOI-4465 b not only expands our knowledge of planets in the far reaches of other star systems but also shows how passionate astronomy enthusiasts can play a direct role in frontier scientific research," Essack said.

The discovery of this planet wouldn't have been possible without international collaborations and several initiatives, including the TESS Follow-up Observing Program Sub Group 1 (TFOP SG1), the Unistellar Citizen Science Network, and the TESS Single Transit Planet Candidate (TSTPC) Working Group.

"What makes this collaboration effective is the infrastructure behind it," Essack added. "It is a great example of the power of citizen science, teamwork, and the importance of global collaboration in astronomy."

The team's research was published on Wednesday (June 25) in The Astrophysical Journal.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments